This June: Influencers

- lindsey4824

- Jun 4, 2025

- 9 min read

Some of the most influential children’s book creators have not only created works that endured across generations, but also pushed stylistic and professional boundaries.

In June we’ll explore the lives and legacies of Gyo Fujikawa, Leo Lionni, Richard Scarry, and Tomi Ungerer. All of them were impacted by World War II and published seminal works in the 1960s –– a period of major innovation and social revolution in many areas, including children’s literature.

Join us for Story Hours and other programming to learn more about these creators and celebrate their inspiring work this month.

Gyo Fujikawa (1908-1998)

As a child, drawing provided Gyo Fujikawa (pronounced ghee-o) both entertainment and solace. She was born in 1908 in Berkeley, California to migrant laborer Hikozo and poet and labor rights activist Yū Fujikawa. Her parents were first-generation Japanese American immigrants, and she often felt isolated attending predominantly white schools.

Thanks to the encouragement and support from several high school teachers, Fujikawa attended the Chouinard Art Institute — now CalArts — where she taught for nearly five years after graduating. From there, she got a job in the promotions department of the Walt Disney Company in Los Angeles before the company relocated her to New York in 1941.

Promotional materials Gyo created for Walt Disney's "Fantasia" film and Beech-Nut cereals.

Fujikawa’s parents and brother were all forcibly sent to Japanese internment camps in California and Arkansas during World War II — a circumstance avoided by Fujikawa because she lived in New York. Throughout the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, Fujikawa worked as an illustrator for a major pharmaceutical company and completed extensive freelance work.

In 1957, Fujikawa illustrated her first children’s book, A Child’s Garden of Verses, written by Robert Louis Stevenson. The book was an immediate success. As per the typical practice at the time, Fujikawa had only been paid a flat fee for her work. Before illustrating more books, however, she became one of the first children’s book illustrators to demand a contractual agreement to receive royalties — both for the already published A Child’s Garden of Verses and her future work. Her negotiation succeeded and she began writing and illustrating her own work soon thereafter.

In 1963, she published her first solo project: Babies. Her publisher at the time was resistant to including non-white children in the book, but Fujikawa insisted and the book itself was another instant hit. This book was likely one of the first to depict multiracial children together. Over the rest of her career as a children’s book creator, Fujikawa wrote and/or illustrated more than 50 books, which have been translated into seventeen languages and are read in more than twenty-two countries.

"In illustrating for children, what I relish most is trying to satisfy the constant question in the back of my mind — will this picture capture a child's imagination? What can I do to enhance it further? Does it help to tell a story? I am far from being successful (whatever that means), but I am ever so grateful to small readers who find 'something' in any book of mine." — Gyo Fujikawa

Before her death at age 90, Gyo also created six stamps for the United States Postal Service, including a one commemorating "Lady Bird" Johnson's "Plant a More Beautiful America" campaign.

Leo Lionni (1910-1999)

Leo Lionni’s children's book career did not start until later in his life, when he used storytelling and illustrations to amuse his grandchildren. He was born in Amsterdam, and his family moved to Philadelphia when he was toddler-aged before moving again and settling in Italy for the rest of his childhood.

Although he studied and received a degree in economics, Leo considered himself an artist in the broadest sense of the word. In the 1930s he worked as a painter and was very active in the Futurism and avant-garde movements. He and his young wife witnessed the rise of Facism in Europe. Leo immigrated to the United States in spring of 1939, followed by his wife Nora and sons, Louis (aka Mannie) and Paolo later that year. Leo’s parents narrowly escaped Amsterdam in 1940 after they found a Star of David painted on their front door one morning, and they joined the rest of the family in the U.S.

Leo began working in advertising, working with major clients and artists including Ford Motors, General Electric, Saul Steinberg, and Andy Warhol. For more than a decade, he worked as the art director for Fortune magazine, also teaching college courses in advertising at universities including Parsons School of Design and Black Mountain College. In both his work and personal life, Leo was embedded in New York’s art community. In 1955 he designed the catalogue The Family of Man photography exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art

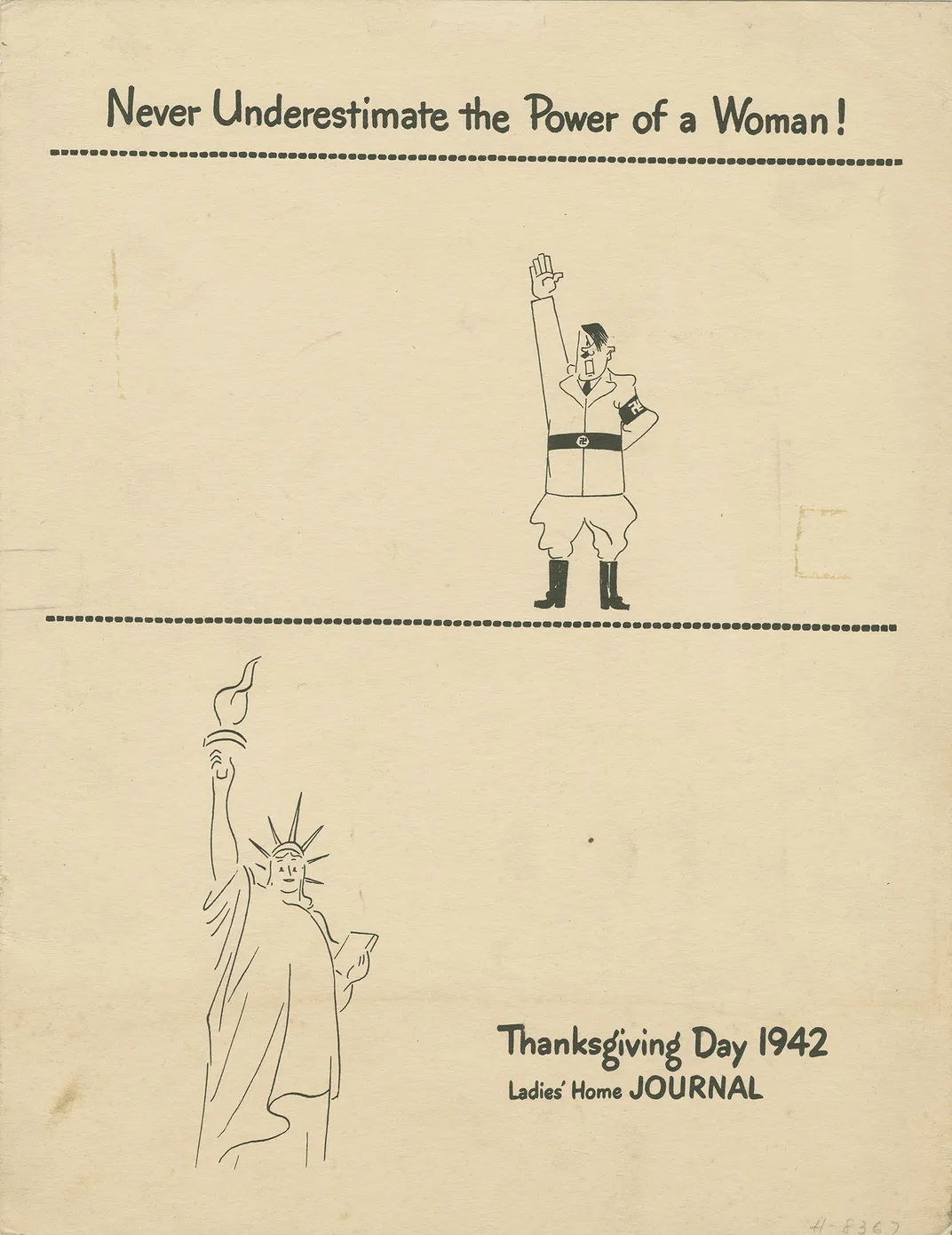

From left: "Never Underestimate the Power of a Woman” campaign for Ladies Home Journal, Ad for Olivetti typewriter, cover for Fortune.

Reflecting on his career and varied creative pursuits (ceramics, mosaic, photography, and flamenco guitar among others), Leo wrote in his autobiography, “I had ‘kept my hands in the pasta,’ as the Italians say. I had been making and doing.”

The concept for Leo’s first picture book, Little Blue and Little Yellow, published in 1959, came from a story he told his grandchildren during a train ride. While telling the story, he did not have any drawing supplies with him, so he tore out shapes from a magazine to use as characters. Leo was one of the first children’s book illustrators to employ collaging as his primary medium, preceding Eric Carle, who is perhaps best known for the practice. Four of Leo’s books were awarded Caldecott Honors, including Frederick, Inch by Inch, Swimmy, and Alexander and the Wind-Up Mouse.

When Frederick was published in 1971, the great psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim wrote that "the fable of Frederick, the dreamer among the little field mice, suggests the psychological truth that when we are in dire need, it is our dreams of happier times which can sustain us.”

Though his books often contained a lesson or moral, they were not didactic. Leo’s expressive collages and text encouraged curiosity, creativity, and change-making.

“All of Leo’s stories are about communities,” Leo’s granddaughter Annie said in a Publisher’s Weekly article. “They all contain a problem, and they all look for solutions. A few of the problems he addressed in his books — like many of our own here in the United States — do not get solved in his stories, but most of them do.”

Leo spent the final decades of his life in Italy creating children’s books and art until his death at age 89.

Richard Scarry (1919-1994)

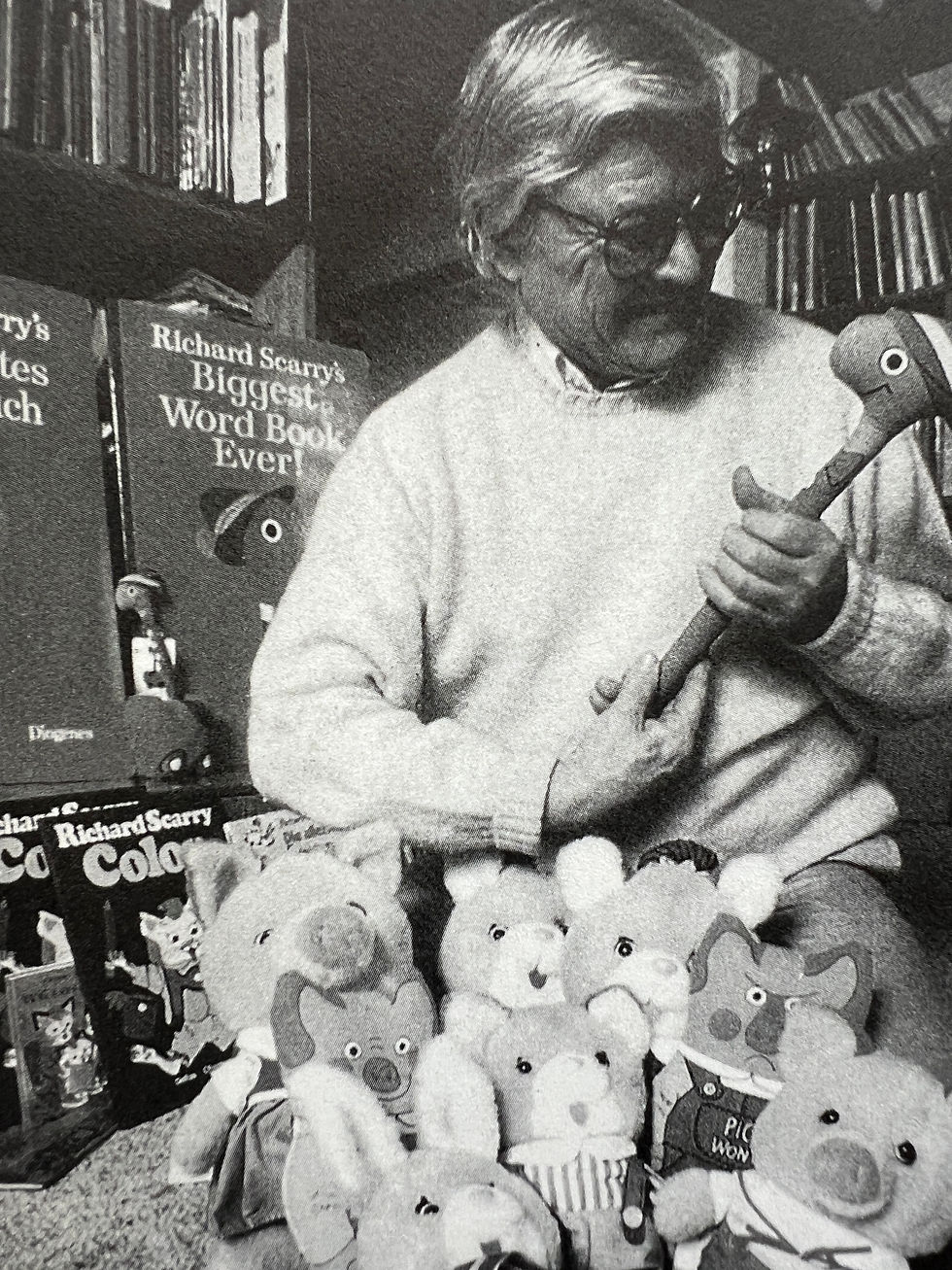

Beyond the millions of copies of books sold globally, Richard Scarry’s enduring impact can also be measured in the instantly recognizable memes featuring illustrations from his extensive “Busytown” universe that features anthropomorphic animals living in harmonious communities.

Richard was born in 1919 in Boston, Massachusetts. His father owned a small chain of department stores, which kept the family afloat during the Great Depression. He loved to draw, and instead of writing out his mother’s grocery list, he drew little pictures of everything she needed. He attributed much of his early love of art to visits with his mother to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

Social media memes using images from Richard Scarry's iconic work.

Never a fan of school, it took him five years to finish high school, and he attended business college briefly before dropping out to pursue an education in the arts. After three years in art school, the U.S. entered World War II and he was drafted into the military. During the five-year stint he had a variety of assignments beginning with radio repair school and ultimately to Algiers where he was an editor, art director, and writer for the Information and Morale Services Section of the Allied Force Headquarters of the North African and Mediterranean Theaters of Operation.

After the war, Richard planned to work as a commercial artist in New York City. It was there that he met and soon married his wife Patsy, a former radio actress from Canada who was working as a writer at an advertising agency.

In 1949 he illustrated his first children’s books, including Two Little Miners written by Margaret Wise Brown and Edith Thacher Hurd. For the next several decades, Richard created more than 70 books with Golden Press. In the early sixties, he wanted to create a different kind of word book for children that was organized by categories instead of alphabetically. In 1963 the Best Word Book Ever was published. It was an immediate success, and with more 1,400 objects young readers spent hours studying the oversize volume.

Richard Scarry illustrated the board book, I Am A Bunny written by Ole Risom. Both it and Best Word Book Ever were published in 1963 and have never been out of print.

Many of Richard’s word books were set in Busytown, where colorful and dynamic animal characters including Huckle Cat, Lowly Worm, Pickles Pig, Mr. Fixit, Bananas Gorilla and Hilda Hippo lived. Using only animals these books were approachable, humorous, and more inclusive.

“It’s a precious thing to be communicating with children, helping them discover the gift of language and thought. I’m happy to be doing it.” – Richard Scarry

In 1969, Richard, Patsy, and their teenage son Huck moved to Switzerland. Since his travels in the military and during their honeymoon, Richard had hoped to live in Europe. There he continued to create, expanding the Busytown universe with books, toys and animated videos.

During his career he published over 300 books with total sales of over 100 million worldwide. Richard died in 1992 at age 74 in Gstaad, Switzerland.

Tomi Ungerer (1931-2019)

Describing himself as an archivist of human absurdity, Tomi Ungerer was a master of satire and charm with a large dose of sophistication. His picture books often depict challenging social issues and histories with a “don’t look away” approach and illustrations that teeter between charming and frightening.

Born in Strasbourg, France, in 1931, Tomi’s childhood was spent in the shadow of the death and poverty of World War II. When he was eight, German Nazis took control of his hometown.

“Living through those times, however, has had a profound effect on me in my adult life and I have become, in my own way, a passionate advocate of peace and nonviolence,” Tomi wrote in the introduction to Tomi: A Childhood Under the Nazis.

His childhood drawings reflect the conflict in his anti-Nazi drawings at home and his schoolwork. On the first page of one of his notebooks, his teacher left a note that his swastikas were “zu klein,” or too small.

Labeled as subversive as a student, Tomi never finished a high school diploma or university degree. He had early dreams of becoming a mineralogist or geologist. He credits most of his “education” to the time he spent hitchhiking around in Europe, doing odd jobs and creating art.

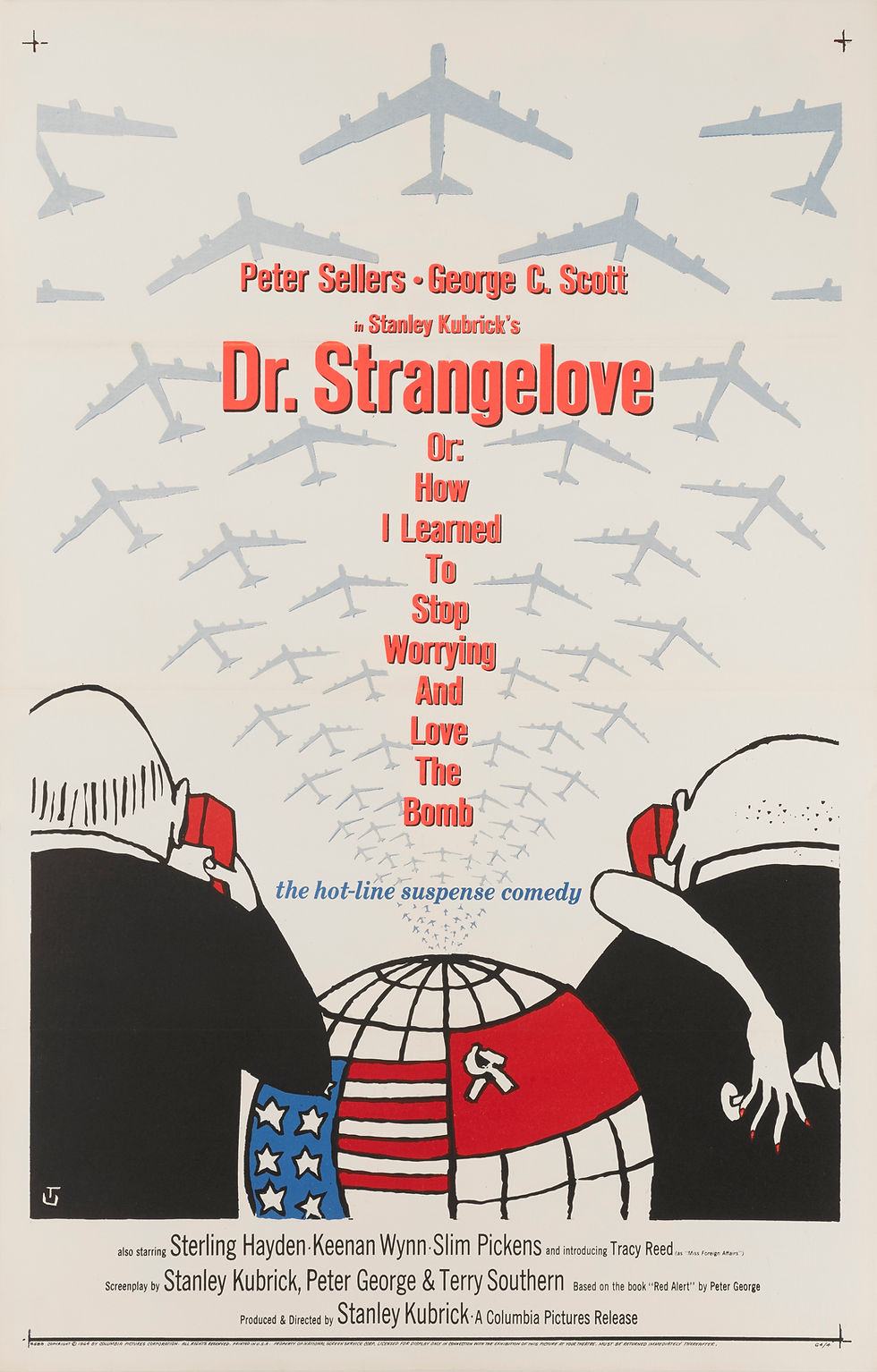

Ungerer immigrated to the U.S. in 1956. In his early twenties, speaking limited English, and with just $60 in his pocket his prospects were bleak. Luckily he met Harper & Row editor Ursula Nordstrom who gave him a $500 advance for his first children’s book The Mellops Go Flying, published in 1957. He continued to produce a steady output of children’s books alongside the adult cartoon work he did for publications including The New York Times, Esquire, Life, Harper's Bazaar, The Village Voice, and more. He was also very involved with a number of social and political causes, including humanitarian campaigns for nuclear disarmament, Amnesty International, Reporters without Borders and European integration.

Perhaps his best-known children’s book, The Three Robbers, about a trio of highwaymen who steal and scare until they meet a little orphan named Tiffany, was published in 1962. What seemingly begins as a fairy tale with, “Once upon a time…” is a powerful story about the relativity of good and evil.

Tomi’s children’s books never speak down to a child — he often said he created books for his own personal enjoyment.

“Children have to be faced with the absurd because the world is absurd.” – Tomi Ungerer

Tomi left the United States for Canada in the 1970s, eventually settling in Ireland where he continued to create children’s books and art. He was an avid collector of mechanical toys, most of which are now housed in the Tomi Ungerer museum in Strasbourg, France, along with a collection of political posters and adult erotica he illustrated throughout his life.

At The Rabbit hOle, Ungerer is one of a few creators to have multiple titles featured. On our second floor there are exhibits for both Crictor and Flat Stanley written by Jeff Brown.

In total Tomi published over 140 books, which have been translated into 30 languages. He died in 2019.